If you are following this series of posts, the chances are that you have already written or started writing a picture book story, or that you are thinking about writing one. And I am concentrating on improving your chances of having the book traditionally published. Traditional publishers want to make money from your book. They think they know what will be most popular with buyers and readers. What makes a best selling book for a publisher is also likely to make a self-published book well liked.

While there are industry expectations and norms, which I'll discuss in future posts, each publisher has a few preferences of their own. Part of your job as a writer who wants to be published is therefore researching publishers to discover what each one likes best - because there's no point in sending a 700 word story to a publisher who only creates books that have less than 600 words.

Analyse every picture book you can find for the

same readership as your stories, 20 or 50 or more, and make notes. Make sure that most of these books have been released over the

last 4 or 5 years (not as reprints of older books). It's particularly useful to hunt out the books that have at least been shortlisted for an award. In Australia, where I live, the Children's Book Council and Australian Speech Pathologists organisations have annual Book of the Year Awards, as do other bodies, and I always check out the winners, runners up and the books that nearly made the podium. These show current editors’ tastes.

You'll quickly discover that picture

books are usually 24 or 32 single page surfaces including the title and legals. Some pages can

be used as flyleaves and paste-downs if the text is short.

For your research in each book, I recommend:

- Note the title

- Write out all the text with what words go on which page

- What reader age is the book most suited to? (The main character is usually portrayed about 2 years older than the expected child reader.)

- Who or what is the main character? How and on what page are they introduced? What is likable about them or what problem do they have - why do we want to follow them through the story?

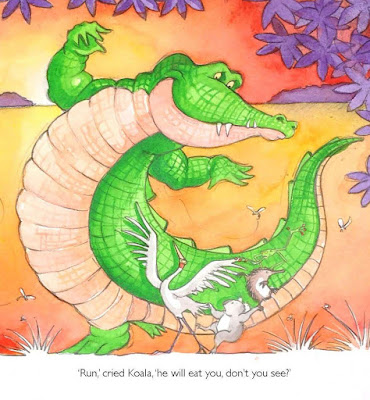

- Describe what the illustrations show on each page - particularly actions. Categorise them like clips of a movie, noting if the picture is a distant shot showing the setting, a medium distance shot showing action or a close up showing emotion.

- What emotion(s) are shown on each page by the illustration or the dialogue?

- Is there something on the page that encourages or forces you to turn over to the next - it could be an illustration of someone or an animal walking out of the picture (where are they going, what will happen to them? Turn over to find out!), or someone having a problem or doing something (what are the consequences?), or are the words open ended, eg ...and then... - so we want to know what happens next.

- Count and note the total number of words

- Note the name of the publisher

- Note the year or date of first publication

You'll discover the word count limit for each publisher, if they tolerate slang, if the text includes long or unusual 'made up words' or not, and much much more. Some publishers don't publish books with talking animals, or over 500 words, or with words that rhyme...

Each publisher has their own style of book - their own brand. No matter how famous you are as an author or illustrator, how many millions of books of yours a publisher has sold, they may still not publish you're wordless sketchbook if they consider that style to be too dissimilar to the books that they're well known for.

So, you are searching for publishers who

print books ‘just like yours’ – length, style, age-range... or you will write and edit your text to suit as many publishers as possible, or you will modify your text according to which publisher you send it to. One of my unpublished stories has a platypus as a main character ...but I may change it to an otter if it is sent to American publishers who only publish stories about animals that live wild in the USA.

In Part 3 I'll start to discuss what makes a publishable story.

Enjoy your research

Peter Taylor

Part 1 of this series can be found at How to Write a Picture Book - Part 1